The Rural Lens

“The rural poor are, in many ways, invisible. They don’t beg for change. They don’t congregate in downtown cores. They rarely line up at homeless shelters because, with few exceptions, there are none. They rarely go to the local employment insurance office because the local employment insurance office is not so local anymore. They rarely complain about their plight because that is just not the way things are done in rural Canada” (Standing Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, 2006, p.v).

Non-metro area (NMA) communities have been categorized a multitude of ways including by status of population growth/density, demographics, proximity to larger centres, and industry/economic base, all of which influence housing dynamics. Rural Southwestern Ontario geographies often leave towns tightly bound by prime agricultural land adding restrictions to development, and the increased cost of rural municipal infrastructure adds an additional price burden.

Although the body of housing industry documentation can be overwhelming, urban centres garner much of the attention based on sheer scale, while little focus has been put on the non-metro perspective. Housing is an intensely local issue, nuances of local need and community influences are significant to understand when evaluating context and solutions. Of the non-metro academic work completed, case studies have highlighted the need for local capacity and leadership to develop enabling environments and place based approaches to non-metro housing needs under what is a complex policy system, however the focus has typically been on the outcome not on what those specific capacities and needed enabling conditions were.

Less populated geographies can be significantly influenced by regional dynamics or single industry decisions, which can leave Councils reacting to imminent pressures rather than planning for a sustainable supply of affordable housing. Challenges with obtaining consistent localized data and comparable data sets down to the granular level of rural communities adds difficulty for housing assessment and planning.

Gentrification is usually reviewed from an urban context however the COVID pandemic has heightened the impacts of gentrification on non-metro communities with an influx of urban residents arriving with higher economic capital, the desire for more space and the newly found encourager of remote work, all in turn elevating housing prices and exacerbating the challenges of meeting local affordability needs and infrastructure investment. Gentrification pressures and lack of local social support services also pushes vulnerable sectors to larger rural centres, putting pressure on these central non-metro hubs from both ends of the spectrum. Due to distances to services, there is a requirement for a mode of transportation, of which public transit has been void in rural areas. Seniors do not have a breadth of downsizing or smaller home tenure options and struggle to maintain the oversized older homes in which they live, giving little option to age in place in their community.

Morris et al (2020) states that "NMA communities, expecting to see large parts of their workforce retiring in the next decade, are concerned with retaining their youth, attracting a new workforce, and enabling their retirees to age-in-place. The current NMA housing stock ticks none of those boxes. It is old, not energy efficient, in need of major repairs, lacks modern amenities and design, and is not accessible or adaptable for those wanting to age-in-place. Ignoring housing issues in non-metropolitan Canada will have serious consequences, including decreased economic potential and increased cost of public services.” Morris proceeds to suggest that NMAs “do not have housing that is suitable and safe for older residents and they do not have housing that is attractive to younger residents. This is a formula for community decline.” Morris summarizes with a clear statement that “the economic sustainability and community wellbeing of non-metropolitan Canada is at risk because the state of housing has become a key constraint on economic and community development.”

Rural areas often have a monolithic landscape of large aged detached single family dwellings, reducing household sizes, and little supply of rental housing. This homogeneic palate of housing form and tenure leads to an increased level of NIMBYism as there has not been significant exposure to positive forms of densification. Residential tenure is focused on home ownership, imposing significant barriers for low income households to save for a down payment, and new affordable construction is rare. There is a mismatch between supply and need.

As our Country is reliant on immigration so too will the non-metro communities be required to welcome newcomers to sustain their economies. Research has shown the significance of housing for initial immigrant settlement, whether they are moving to rural areas directly from their home country or as a secondary move within Canada, on social connection, community integration, and in turn desire to stay. For smaller communities to entice newcomers they must embrace diversity and become welcoming, part of that is having appropriate housing available.

NMA Housing & Homelessness Reports show the drastic rise in housing prices have created a rapidly divergent trend with incomes, creating challenges for not just low but also moderate income households. In Stratford, Perth County and St. Marys (City of Stratford, 2020) up to the 40th income percentile cannot afford any market level rent for any type of dwelling, and you must be in the 70th income percentile or higher to afford a two bedroom unit, if you can find one.

NMA employers are desperate for staff and recognize the significant influence attainable housing stock plays as a contributing factor to the local labour shortage. Rural economic vitality will be influenced by the ability to provide needed housing stock.

A review of stakeholder feedback throughout my research highlighted the following experiences and perceptions of non-metro areas when it comes to housing:

We have a dominant single family dwelling portfolio, a monolithic landscape of large aging homes, and we’re conservative, skeptical, and even sometimes combative with diversity and density options;

·We have a desire to protect agricultural lands, which means we will have to densify within our villages, towns, and urban boundaries – up, back, beside, or inside;

We are not great with change;

We have over housed seniors with minimal downsizing options;

We have limited rental housing supply and it is often stigmatized;

Everybody knows everybody, these interconnections can be very helpful as well as a hindrance;

We have an added social perception where we think everyone should work hard and be able to buy a house and take care of themselves;

We are in dire need of workforce, and everyone we have is working;

Gentrification has come upon us, those moving out from the more urban areas are aiding the rising cost of housing, but we need and want new residents;

We have limited depth or breadth of resources, infrastructure, services, and capacity;

We have not yet made housing a significant priority that we view our choices, actions, or decisions through the lens of how does this help or hinder someone having a place to call home, and that they actually deserve one as much as we do; and

We have strong social connections, community allegiance, and can be nimble, responsive, innovative, and action oriented.

City of Stratford Social Services Department. (2020). Stratford, Perth County, and St. Marys Housing and Homelessness Plan 5 Year Update 2020-2024.

Morris, M., Good, J., & Halseth, G. (2020). Building Foundations for the Future: Housing, community development, and economic opportunity in non-metropolitan Canada. Community Development Institute at the University of Northern British Columbia.

Housing Affordability | Why Should We Care?

Why Housing?

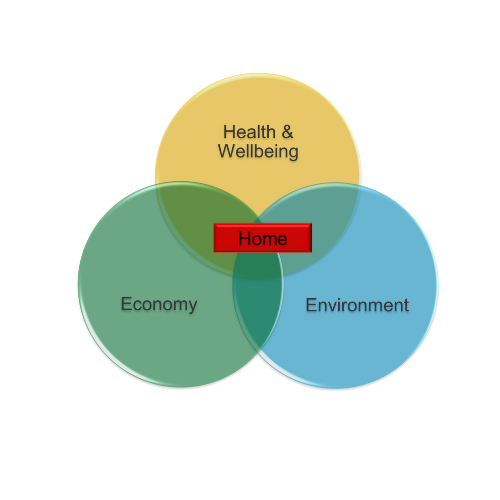

The issue of housing is one that is not only felt at an individual level but on a global front. The alert continues to be sent out to the many organizations, both public and private, that have influence or bare impact from the dire need. Negative implications to society are broad including health and wellbeing, environmental, and economic. This wide span of influences and impacts opens the door to a deep pool of potential partnerships to activate solutions.

Health & Wellbeing

It has been agreed globally that access to stable housing is fundamental to living a decent life, that it is a basic human need and central to wellbeing. It is a human right and essential to sustainable community development, human development, and social cohesion.

The audiences in need of housing are broad, including the aging over housed and isolated, multigenerational families, young professionals, newcomers, and many front line service workers; their housing needs are diverse but options must be available and attainable. Each of these groups develop unique social struggles as a result of housing instability but often include elevated stress, depression, social exclusion, illness, and disease.

Housing disadvantage can actually be used as a predictor of poor health outcomes.

The lack of appropriate housing disproportionately impacts low to moderate income earners that are required to spend a larger percentage of their income on shelter which often leads to living in poor quality or overcrowded dwellings, and negative consequences due to the forced reduction of available resources for food, education, health and recreation.

Environment

Environmental consequences and carbon cost from the expansive scale of our large lot single family residential trends include increased direct and indirect emissions, natural resource usage, reduction in greenspace, and environmental impacts as a result of increased fuel and commuting requirements. All posing a challenge to our goal of becoming a lower carbon economy.

Economy

Housing affordability challenges are now encroaching on higher income brackets. Although no longer

targeted solely at the impoverished, from a socio economic perspective housing is still heavily referenced as a primary tool to reducing poverty, being listing as one of the top game changers.

A poorly functioning housing market, with a lack of appropriate available housing also leads to reduced opportunity for mobility, which impacts growth potential and creates significant challenge to meeting workforce needs. And renters are stuck, with lack of availability and vacancy decontrol they cannot move to a closer or more suitable space as current market rates await them. The lack of availability has also created a highly competitive market both financially and in broadening the landlord’s choice of tenants.

With one of the lowest jobless rates in Ontario, the Four County Labour Market Planning Board (Bruce, Grey, Huron and Perth counties) has suggested that housing has risen to the top as the number one workforce challenge for the region”. These unmet needs impact many layers of our economy.

As a sector, the housing industry is also a substantial contributor to the economy both from a GDP scale as well as personal investment, so the challenges of affordability struggle to find priority in a market driven economy.

The Dynamics of Housing

There has been much research and discussion regarding the influential power of one pillar over the other...but we have landed in a place of mismatch. This certainly did not occur overnight, it has been a long history of policy decisions and social priorities in a market driven economy that have failed housing affordability. It is no longer someone else's responsibility, we all have a role to play.

Supply

Is it the Right Supply? Not everyone follows the linear housing continuum, and home ownership is not the only option. Our housing system comprised of a single family dwelling focus has not evolved to consider our changing demographics of seniors, singles, single parents, young professionals, service workers, multigenerational, and more transient generations confident with technology and shared spaces. We need to offer choice to serve all markets; do we have density, co-living options, secondary suites, tiny homes, bungalows, condos, rentals, etc. More of the same faster is not going to address the challenges of housing affordability; early in the process, we need to include considerations for what supply our communities need and how to manage for long term affordability. Real estate with a socio-economic approach. We also need to ensure preservation and renewal of the affordable stock that we’ve got – we are currently losing far more affordable housing stock than we are gaining and replacement costs would far exceed the entire NHS budget. Does your community have attainable stock that is at risk of going to market? We need more housing, but it has to be the right housing to meet the unfulfilled demand that does not have the ability to influence the market.

Demand

We have financialized and commodified housing, instead of humanity, we have created a supercharged targeted demand but need to reflect on the needs of all. Have we forgotten those that do not have the income or wealth to create effective market demand?

Financialization has also contributed to the transformation of the Canadian housing system whereby housing is bought, sold, and priced as an asset for speculation, a commodity through which to accumulate wealth and leverage debt, instead of being rented or sold as a social good. Real estate investment trusts (REITs), corporations, and investors at the local, national, and global scale have taken to buying low rental housing, forcing out tenants and either redeveloping or increasing rents and purchase prices putting them out of reach of those that need it; and renters are stuck, there are no provisions ensuring alternative accommodations if evicted and they are then faced with full market rates, if they can even find a space. And, access to low interest borrowing power has not helped those that are in need of housing.

Policy

This is a decades old problem across the Country and particularly in Ontario where the ball was dropped with devolution between 1994-2017. We have been left with a poorly functioning fragmented amalgam of policy and funding initiatives and a system that was not designed. All levels of government play a role in housing, and they have recognized the crisis, but actions have thus far failed to produce the needed results. The risk of changing government priorities and lack of clear policy and funding continuity has proven tragic for many. But locally we have influence, and policy can be enabling!

Community

Housing is inherently a community issue as it requires land, which is locally defined. We cannot wait for senior levels of government to design and implement a system that works. We must continue to advocate but not wait. If we don't move locally, there will be too many casualties with impacts to the social and economic fabric of our communities. Rural communities are rarely the focus of housing research, policy, or dialogue, but we have the power...do we have the will? I am not under the illusion that there is one magic solution to fix it all and nor were any of the industry leaders or stakeholders that I have spoken to, but I do have absolute belief in the strength of community, and my research has demonstrated it on a practical level.

Housing Affordability | How Did We Get Here?

So how did we get here? As an historical policy and societal overview of our current state of housing affordability challenges:

1919 – our first public sector home ownership initiative to support Veterans

1946 – CMHC was established with efforts to use public funds to enable mortgages and home ownership

1964-1993 - Public/Community Housing – Federal / Provincial collaboration & philosophy to provide housing at a reasonable cost and a social right. Beginning of non-profit and coop sector. Approximately 500,000 units of social housing stock built in Canada. (Hulchanski & Shapcott, 2004)

1970’s – condo ownership legislation, speculation increased price of homes/ land with baby boomers entering housing market; significant interest rate increase (21% in 1981)

1984 – conservative leadership, start of a 10 year steady decline of federal funds for housing, ignoring expert recommendations; reduction in federal social assistance funding, federal downloading and reduction of provincial transfers…federal budget surplus and tax reductions for highest income earners, at the expense of social spending

1993 – complete federal withdrawal on non-market housing; legacy projects with operating or mortgage agreements expiring. Leading to current loss of stock concern.

1994-2017 – Devolution

Federal devolution to province, provincial (Ontario) investments decreased, cancelled projects (17,000 coop/np units) and lost units (45,000 private rental, 12,300 social)

Ontario is the only province that transferred administration of legacy housing programs to the municipal level

The dismantling of the federal social housing supply program and lack of coordinated strategy, left the provinces and municipalities to burden the direct and indirect costs related to the fall out, including physical and mental health, social services, and safety implications

In 2004, Hulchanski (2004) stated that approximately 5% of Canada’s households lived in non-market social housing, the smallest social housing sector of any Western nation except the United States which had 2%; compared with 40% in the Netherlands, 22% in the United Kingdom, and 15% in France and Germany

Since 2001, BC and Quebec have contributed over three quarters of all new affordable housing supply in Canada with the key attributes of a systems approach, institutional infrastructure, and government and community capacity leading to the creation of a collaborative conducive ecosystem to enact and enable creative, flexible, and effective solutions while also sustaining existing stock (Pomeroy, 2019)

2017–today – Re-engagement

National Housing Strategy (2017) – first time the Canadian government has recognized housing as a fundamental human right through legislation

However data shows that between 2011 and 2016 for every one new affordable unit created, fifteen existing private affordable units were lost; the cost to build and replace these 322,600 lost units would be more than six times the entire NHS budget (Pomeroy, 2020; Canadian Housing Policy Roundtable, 2021).

In 2017, Canada’s social housing sector totaled approximately 650,000 units representing just under 5% of all of housing and almost one fifth of all rental housing (Pomeroy, 2017). Ontario’s regulatory housing framework is ‘confusing, and impossible to navigate’, there are many ministries, acts, regulations, policies, and interests that are not aligned on requirements and processes, and funding programs are oversubscribed and without a long term vision or strategy.

We are in a situation as Hulchanski (2005) suggests, of having an incomplete housing system in Canada where the market demand for housing is addressed however the social need is not. Those with too little wealth to stimulate a market demand are ignored.

References

Canadian Housing Policy Roundtable. (2021). Three Polices Needed for a Healthy Housing System.

Hulchanski, J.D. (2005).Rethinking Canada's Housing Affordability Challenge. Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto, for the Government of Canada’s Canadian Housing Framework Initiative.

Hulchanski (2004). How Did We Get Here? The Evolution of Canada’s “Exclusionary” Housing System (Ch.11) in D. Hulchanski and M. Shapcott (Ed) Finding Room: Policy Options for a Canadian Rental Housing Strategy. Centre for Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto.

Hulchanski, D. (2004). What Factors Shape Canadian Housing Policy? The Intergovernmental Role in Canada’s Housing System (Ch. 10) in R. Young and C. Leuprecht (Ed) Canada: The State of the Federation 2004, Municipal – Federal – Provincial Relations in Canada.Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University by McGill-Queens University Press.

Hulchanski & Shapcott. (2004). Introduction: Finding Room in the Housing System for All Canadians (Ch.1) in D. Hulchanski and M. Shapcott (Ed) Finding Room: Policy Options for a Canadian Rental Housing Strategy. Centre for Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto.

Pomeroy, S. (2020). Augmenting the National Housing Strategy with an affordable housing acquisition program. Focus Consulting Inc.

Pomeroy, S., Gazzard,N., & Gaudreault, A. (2019).Promising practices in affordable housing: Evolution and innovation in BC and Quebec. Canadian Housing Policy Roundtable.

Pomeroy, S. (2017).Discussion Paper: Envisioning a Modernized Social and Affordable Housing Sector in Canada. Carlton University Centre for Urban Research and Education.